Last year, Israel’s ambassador to the U.S., Michael Oren, stated that “an Iranian bomb can wipe Israel off the map in a matter of seconds.” Others are less pessimistic.

“People tend to be fatalistic about a nuclear attack. They say, ‘There’s no way to cope with a nuclear bomb.’ But that’s not true,” says Oren Skurnik, who sells private nuclear shelters in Israel. “It’s perfectly clear that if an event like that occurs in a built-up area, many people will be hurt. But that is not necessarily true for less populated areas. It doesn’t mean a state won’t remain – that those people who remain will not be able to survive. People think it’s a matter of a doomsday scenario, but that’s not necessarily the case.”

The local nuclear-shelter market is still in its infancy and is considered the privilege of the rich or obsessed.

“A nuclear strike is a situation that invites plenty of repression,” Skurnik explains. “Normal people don’t get up in the morning and start thinking about such things. It’s a subject that is naturally not very pleasant to consider.”

Most of Skurnik’s business involves selling ventilation and filtering systems for use in the event of biological and chemical warfare, under the trade name “Noah’s Ark.” Requests for full-scale nuclear shelters are relatively rare – only a handful a month.

What turns a protected space into a nuclear shelter?

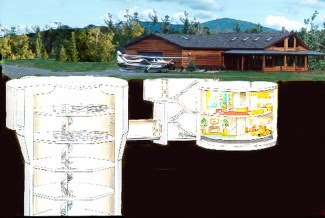

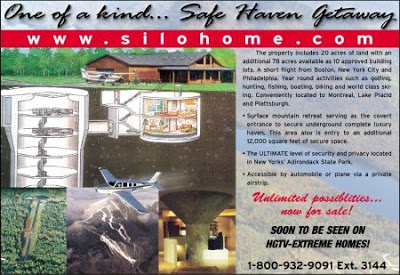

Skurnik: “To begin with, a nuclear shelter has to be underground, with metal parts that can withstand high levels of shock waves. In addition, the planning of a nuclear shelter has to take into account a long stay of a week at least. That requires water and sewerage infrastructures, storage space, support systems. So when you sit with someone and plan a nuclear shelter, it starts with questions like: What type of kitchen would you like? What food will you have? How big a bed will you have? What size is the generator and what fuel reserves will there be? There are elements here that have to sustain people who will be cut off for a relatively long time [from life outside]. A basic shelter like this costs about NIS 100,000. People think it is a luxury reserved for the very rich, but not everyone who contacts me is wealthy. It’s a personal thing. Some people are really scared.”

In 2002, the Israeli National Security Council, a unit in the Prime Minister’s Office, announced the construction of a protected space, described as “a national center for crisis management.” The underground site, built inside a hill on the outskirts of the capital, and apparently intended to be linked by tunnel to the Kirya, the government compound in central Jerusalem, is meant to allow the government to continue functioning during chemical, biological or nuclear attacks. The facility’s estimated cost is hundreds of millions of shekels, and its maintenance is the responsibility of the committee for security facilities (part of the Interior Ministry) and of the Defense Ministry. The tunnel contains conference rooms, offices and halls, along with computerized control systems that can relay information on events above-ground.

When work on the huge shelter began, environmental groups protested that the construction of “the prime minister’s escape tunnel” was wreaking destruction in what is called the Valley of the Cedars, one of the few green lungs left in the Jerusalem area. Others were critical of the idea that the country’s leaders would save themselves during a disaster by means of an underground shelter.

“The bunker is a project that is shrouded in great mystery, but on the other hand it’s an open secret, because a great many Jerusalem residents are familiar with it and know where it is,” says Dr. Oded Lowenheim, a lecturer in the international relations department of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who has researched bunkers in Israel.

“It is meant to hold a few hundred people from all kinds of agencies who are supposed to oversee life during a situation of collapse,” he says. “It’s intended for a variety of situations, from the firing of Qassam rockets and Katyushas to the most extreme scenario. I think many of those who are meant to be in the bunker don’t even know it.”

Let’s say the government survives – what then?

Lowenheim: “I ask that, too. I am not sure that rational thought preceded the construction of this structure. It sounds more like it’s being built simply because, in the planners’ minds, every country needs such a bunker. It seems to me that what underlies the project in part is a psychological need to feel protected even in the case of nuclear war, which from Israel’s point of view will amount to an absolute holocaust. The bunker reflects the state’s inability to recognize that there are situations in which it will no longer exist. That feeling underlies the construction of a structure like this, just as the pharaohs built themselves pyramids and other burial edifices: They thought they [the structures] would ensure their future in the next world, or maybe they could not come to terms with the idea that there is no life after death. After all, those in the bunker will have nothing ‘to command and control’ after a nuclear holocaust in Israel. Hence it is a response to a psychological need.”